The Up-End Migraine Project reveals key gaps in episodic migraine care, aiming to drive change and improve treatment options for patients through insights from both providers and patients.

Chronic Migraine and Comorbid Conditions: What You Need to Know

Chronic Migraine and Comorbid Conditions: What You Need to Know

From mood to sleep and gastrointestinal disorders, many conditions can also occur with chronic migraine. Learn about the link — and how you can better manage all of your conditions.

November 1, 2022

Karyn Repinski

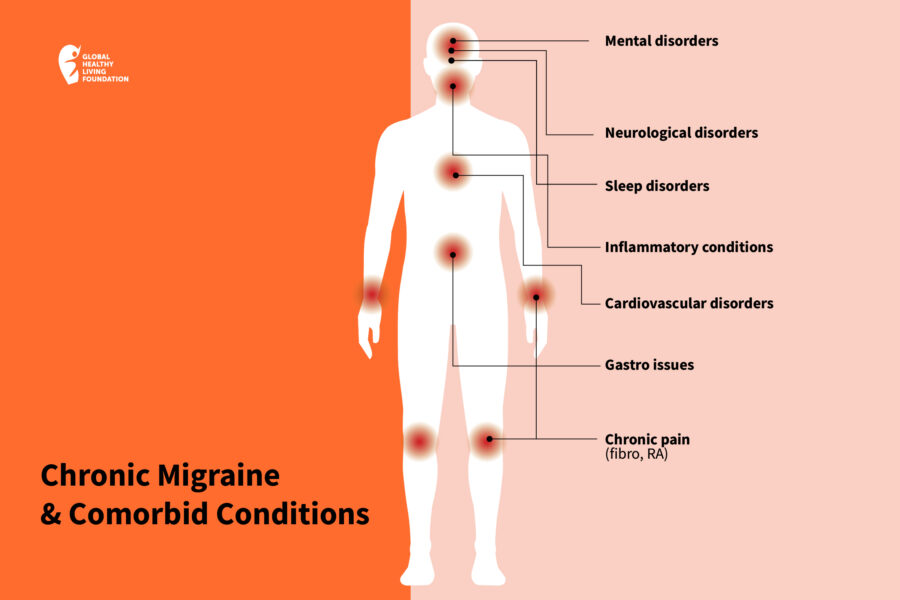

Having a migraine attack once in a while would be bad enough, but people with chronic migraine can live half of their lives dealing with these debilitating symptoms. Adding insult to injury, the neurological disorder seems to co-exist with a wide variety of other health conditions. In medical terms, when two or more chronic medical conditions occur together at a greater than coincidental rate, they’re considered comorbid. So, in addition to your primary health concern, having a comorbidity means you also have another separate disease. The two conditions don’t cause each other; they simply occur at the same time.

Comorbidities Are Common with Chronic Migraine

The statistics on chronic migraine and comorbidity are pretty staggering: Nearly 88 percent of people with chronic migraine have at least one comorbid condition, while 39 percent have four or more comorbid conditions.

Comorbidities can also occur with episodic migraine, which is defined as 14 or less headache days a month, and their presence has been found to increase the risk of transforming from episodic migraine to chronic migraine — something that occurs in about two percent to three percent of people each year.

Many conditions are comorbid with migraine; more than 75, according to the Association of Migraine Disorders (AMD). “We’ve identified migraine comorbidities in almost every body system, including the cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, neurological, and integumentary,” says Kylie Petrarca, RN, Associate Program Director for the AMD, who lives with chronic migraine. “People of all ages and stages of life are affected, including children, adults, the elderly, and people during pregnancy.”

Not surprisingly, Dawn Buse, PhD, a licensed psychologist and Clinical Professor of Neurology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, has found in her research that people with chronic migraine were nearly three times as likely to report poor or fair health as those with episodic migraine, which could be related to having co-existing conditions.

A Closer Look at Comorbidities

Migraine has what’s known as a bidirectional relationship with a host of co-existing conditions. That means that people with the neurological disorder are more likely to develop the other disease and vice versa.

This can indicate that the two conditions share defects in the systems that regulate certain chemical messengers in the brain. It can also be the result of genetics and environmental triggering factors. Emotional stress or psychological distress, such as anxiety or depression, could also increase someone’s susceptibility to migraine and the co-existing condition.

The good news is that sometimes, effective management of the conditions can help reduce the incidence of migraine and the comorbid condition.

Mental disorders

The most common comorbidities with chronic migraine are a wide range of psychiatric disorders, including anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorder. “People with chronic migraine are twice as likely as those who experience episodic migraine to have depression and anxiety,” says Dr. Buse.

For many people, depression or anxiety begins months or years after they develop migraine — partially because migraine can be so debilitating, Dr. Buse explains. Others develop migraine after living with depression or anxiety for some time. The connection may be due to low levels of neurotransmitters (brain chemicals like serotonin and dopamine) or genetic and environmental factors that may increase your risk of mood disorders and migraine.

The link between the conditions may not be clear, but it’s very strong: Between 30 percent and 50 percent of people with chronic migraine also have anxiety — that’s two to five times more prevalent than in the general population and much more common than in people with episodic migraine, according to AMD. Among anxiety disorders, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and panic disorder are the most strongly linked with migraine.

People with migraine are over 2.5 times more likely to suffer from depression compared to people without migraine, and the association is even stronger for people with chronic migraine and people who have migraine with aura, the temporary sensory disturbances that can occur before a migraine attack. Depression and migraine are so closely linked that they share what’s called a bidirectional relationship, which means that one increases the risk of the other.

A bidirectional relationship also seems to exist between migraine and bipolar disorder, which is characterized by drastic mood swings. People suffering from migraine with aura are three times more likely to suffer from bipolar disorder than the general population, and conversely, about one-third of people with bipolar disorder have migraine.

Cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disorders (CVD) are more often associated with chronic migraine than with migraine that occurs less frequently. Severe headache pain, a symptom more common in chronic migraine, is associated with an increased risk of peripheral artery disease, high cholesterol, and hypertension (high blood pressure), according to researchers. According to Dr. Buse’s research, one-third of chronic migraine patients are diagnosed with hypertension and high cholesterol, and 10 percent are diagnosed with coronary heart disease.

Both migraine and migraine with aura are associated with CVD and risk factors for CVD. In a large Danish study of 51,032 patients with migraine and 510,320 matched controls followed over 19 years, migraine was associated with an increased risk of several heart-related events, including myocardial infarction (aka heart attack), stroke, venous thromboembolism, atrial fibrillation, and atrial flutter. The associations were stronger among women, who tend to experience more migraine attacks, and in those with aura.

Neurological disorders

If you have epilepsy, you’re more than twice as likely to develop migraine as someone who doesn’t. And as there’s a bidirectional relationship between the two, the reverse is also true. People with migraines are more than twice as likely as others to have epilepsy (a state of neuronal hyperexcitability that increases the risk of both disorders may explain the comorbidity), though they’re most likely to develop epilepsy due to another risk factor, such as a head injury or stroke.

Restless leg syndrome (RLS), a sensory neurological disorder where you feel an uncomfortable sensation in your legs and have an uncontrollable urge to move them, is more common among people with migraine. Reported prevalence rates range from 8.7 percent to 39 percent. A genetic variant is suspected of causing the increased risk of RLS in people with migraine.

Sleep disorders

Whether or not migraine and insomnia have a bidirectional relationship (it’s possible due to the overlapping of some disordered physiological processes and shared anatomy with the brain), getting adequate shut-eye can be a real challenge for people living with migraine.

According to the American Migraine Foundation, they are eight times more likely to experience sleep disorders, such as sleep apnea and insomnia, compared to the general public. It’s even harder for those living with chronic migraine, who — likely because insomnia is a risk for migraine chronification — report having almost twice the rate of insomnia as those with less frequent headaches.

Research also finds that people with chronic migraine are at high risk for sleep apnea, a sleep disorder in which breathing repeatedly stops and starts. Sleep apnea is more common among people who are overweight or obese, and there are links between migraine and obesity, with weight gain increasing the likelihood of chronic migraine.

Respiratory conditions

People with asthma and allergy/hay fever were twice as likely to experience migraine, according to Dr. Buse’s research. One study revealed that people with asthma who also experience occasional migraines may be two times more likely to develop chronic migraines than those who don’t have asthma. Those with severe asthma are three times more likely to progress. The bidirectional relationship between the two conditions can be explained by many factors, including environmental factors, such as air pollutants, that can aggravate asthma and increase the rate of emergency room visits for migraine.

Chronic pain

People with chronic migraine are twice as likely to have chronic pain, according to Dr. Buse. About one-third of chronic migraine patients have arthritis, and the risk of arthritis goes up with increasing migraine frequency. One explanation for the link is inflammation, which can lead to the release of brain chemicals that include a cascade of inflammatory responses in brain tissues, explains Gretchen Tietjen, MD, professor emerita of neurology at the University of Toledo, in this Migraine Again article.

Chronic migraine is also tied to fibromyalgia, a chronic condition that causes widespread pain throughout the body. In one study that looked at patients with headaches, the frequency of fibromyalgia was significantly higher — and the symptoms more severe — in those with chronic migraine than in those with chronic tension headaches. In addition to frequently co-existing and sharing a bidirectional relationship, chronic migraine and fibromyalgia are associated with significantly more anxiety, depression, and insomnia when experienced together, compared to those with chronic migraine alone.

Gastrointestinal issues

Research shows that those with migraine have a high prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), ranging from 4 percent to 40 percent, according to AMD. Both conditions affect the gut-brain axis, and a disruption to it — for instance, due to levels of serotonin, which are low in the gut in IBS patients and that fluctuate in people with migraine. This could be a plausible connection between the comorbidities, according to researchers who found that those with IBS were 2.25 times more likely than control subjects to experience migraine.

Autoimmune diseases

The link between rheumatoid arthritis, a chronic inflammatory disease, and migraine is not completely understood, but inflammation is believed to play a key role, says neurologist Peter McAllister, MD, Co-founder and Chief Medical Officer of the New England Center for Neurology and Headache in Stamford, Connecticut.

“Migraine is a loop from the brain out to the peripheral pain nerves secreting this ‘inflammatory soup,’ and then back into the brain,” he explained during a recent interview at the Migraine World Summit on the link between autoimmune disease and migraine. “We know that autoimmune disease secretes all sorts of inflammatory bad guys — cytokines, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, leukotrienes — and there’s an overlap there.”

This tendency to turn on and have a limited ability to dampen inflammation, he says, is the tie between the two.

There also seems to be a link between migraine and celiac disease, which is often reported as the first symptom of the autoimmune disease, according to a 2018 review of studies. People with celiac disease, which also affects the gut-brain axis, appear to have headaches and migraine at a much higher rate than the general population. Conversely, those with migraine are more likely to have celiac disease. In a 2019 study, 32 percent of people with celiac disease experienced migraine without aura, while 15 percent experienced migraine with aura.

Managing All Your Conditions

The good news with migraine and its comorbidities is that they’re all treatable conditions and treating each condition may help the other.

To create a safe and effective treatment plan, it’s important for your practitioner to know all of the health issues you experience along with migraine. “A good medical evaluation has to ask about anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, and other medical problems,” says Edmund Messina, MD, a neurologist and headache specialist at the Michigan Headache Clinic in East Lansing, Michigan, in a Facebook Live event hosted by the American Migraine Foundation. “A good first visit history really should take an hour or two, if it’s done right, and you’re going to find all the things that can trigger or interfere with your care of that patient.”

Depending on what comorbidity or comorbidities you experience, you may want to ask your provider about referring you to a headache specialist or a host of providers — for instance, a cardiologist or sleep specialist. “Interdisciplinary care is a great way to help manage migraine and other comorbidities,” says Petrarca.

It’s important for your treatment plan to be coordinated between all of your providers. This is especially true when it comes to medications. “Some comorbidities may interfere with the medicines that work in migraine or may cause more headaches or negatively interact with the medicines,” says Dr. Messina. On the flip side, “several of the approved preventative therapies for migraines may offer the opportunity for therapeutic ‘twofers,’ so that in addition to helping migraine, they may also help depression or cardiovascular risks,” says Dr. Buse.

Finally, remember that lifestyle and behavior play a major role in migraine prevention, as well as in preventing the conditions that occur along with it. Stress reduction is critical, since stress is the most prominent migraine trigger.

Maintaining a regular sleep schedule is also helpful. “The migraine brain wants things to be consistent,” says Brad Torphy, MD, lead doctor for the Chicago Headache Center and Research Institute. “Anything that interferes with consistency can lead to migraine attacks.” When it comes to migraine triggers, there are many — like the weather — that we can’t control, he says. “We try to control what we can.”

Hear From More Experts and Patients Living with Chronic Migraine

Talking Head Pain is a podcast that confronts head pain, head on. Brought to you by the Global Healthy Living Foundation and hosted by migraine advocate Joe Coe, this show explores how people living with migraine, cluster headache, and other types of intense pain find ways to better manage their disease. Listen here.

Sources:

Buse, DC, et al. Comorbid and co-occurring conditions in migraine and associated risk of increasing headache pain intensity and headache frequency: results of the migraine in America symptoms and treatment (MAST) study. J Headache Pain. 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-1084-y.

Interview with Kylie Petrarca, RN, Associate Program Director for the Association of Migraine Disorders.

Interview with Dawn Buse, PhD, Clinical Professor of Neurology at Albert.

Interview with Brad Torphy, MD, lead doctor for the Chicago Headache Center and Research Institute.

Katsarava, Z, et al. “Defining the Differences Between Episodic Migraine and Chronic Migraine.” Current Pain and Headache Reports. February 2012. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-011-0233-z.

The Migraine Comorbidity Library. Association of Migraine Disorders. https://www.migrainedisorders.org/comorbidities/.

Migraine Co-Morbidities. BMJ Talk Medicine. https://soundcloud.com/bmjpodcasts/jnnp-podcast-april-2010.

Sleep Disorders and Headache. American Migraine Foundation. April 25, 2019. https://americanmigrainefoundation.org/resource-library/sleep/.

Wang, L, et al. “The Comorbid Relationship Between Migraine and Asthma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Studies.” Frontiers in Medicine. January 13, 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.609528.

SUBSCRIBE TO GHLF

RELATED POST AND PAGES

_

Was this article helpful?

YesNo