Enhancing Adult Vaccine Uptake: Challenges in Shared Clinical Decision Making and Risk-Based Recommendations

A Patient’s Guide to Vaccine Advocacy

A Patient’s Guide to Vaccine Advocacy

For more than 200 years vaccines have been regarded as one of medicine’s miracles, responsible for saving more lives than perhaps any other medical advance in history. Recently, however, the conversation about vaccines has dramatically changed. Thanks to widespread misinformation, some people — parents of young children in particular — have become suspicious of lifesaving immunizations.

Unfortunately, this “vaccine hesitancy” threatens not only the health of unvaccinated children, but of many others as well. That is why it is so important for pro-vaccine advocates to become educated about the science and public health implications of vaccines and fight to ensure as many people as possible receive their recommended immunizations.

This guide to vaccine advocacy contains current information and resources on vaccine safety, explains the importance of vaccines to everyone in a community, and provides information on how to counter the growing ignorance about vaccines that is now threatening public health in your community and around the world.

Jump to the section:

Understanding the Vaccination Controversy

The Problem with Non-Medical Vaccine Exemptions

Facts About Vaccines

Debunking the Dangers of Vaccines

The Basics of Vaccine Science

State Progress on Vaccination

UNDERSTANDING THE VACCINATION CONTROVERSY

How Vaccine Fears Began

Considering how beneficial and lifesaving vaccines are, it’s rather shocking that so many people are now opting to not receive them. Yet vaccines have been somewhat controversial from the start. In fact, in 1796 when Edward Jenner invented the smallpox vaccine, there was an anti-vax movement among people who didn’t understand the importance of the discovery.

More recently, the public has been frightened by bogus scientific studies that purported to link vaccines with scary — and unfounded — health risks. In 1982 an NBC documentary examined a British controversy linking the pertussis (whooping cough) vaccine with seizures in young children. Whooping cough is a potentially fatal disease that can cause lung problems. Although doctors criticized the show as dangerously inaccurate, vaccine fears spread.

In 1998, Andrew Wakefield, a British gastroenterologist, published a now-infamous study in the prestigious British medical journal The Lancet. Since discredited and withdrawn, the paper falsely associated the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine with autism.

By that time, many people had never seen a case of measles, mumps, or rubella because vaccines had nearly eliminated those diseases. But the developmental disorder autism was gaining awareness on the public radar. Around the same time, there was a growing trend toward “natural” parenting. Drug-free childbirth came back in vogue. Parents started using cloth diapers, making their own baby food, and buying more organic products. Instead of being seen as the very natural, important health tool that they are, vaccines became linked with the artificial and chemical.

How Vaccine Fears Spread

The easy spread of misinformation on the internet and social media played a big role in disseminating fear about vaccines. Vaccine resistance movements started springing up in almost every state. Anti-vaccine advocates started targeting grieving parents who were looking for an explanation for the death of a baby or young child — often when the infants’ deaths had been attributed to co-sleeping or Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) — to turn them into crusaders against vaccines. Parents of children on the autism spectrum were also targeted to become anti-vaccine advocates. In spite of no sound scientific studies being able to confirm the links between vaccines and these health issues, fear started winning.

It didn’t help that celebrities — who are obviously not medical experts — started weighing in. Actors Rob Schneider and Jessica Biel argued against California legislation aimed at increasing vaccination rates by banning non-medical exemptions. Others such as Jenny McCarthy, Jim Carrey, Alicia Silverstone, and Kevin Gates publicly expressed their concerns about vaccine safety. These voices started drowning out the recommendations of pediatricians and infectious disease experts who have dedicated their lives to studying vaccines and improving public health. Parents might take their children to the pediatrician a few times a year, but they were constantly being bombarded online and on social media with anti-vaccine messages.

The Consequences of Vaccine Ignorance

The number of U.S. children who have not received any vaccines by 24 months old has been gradually increasing over time — from 0.9 percent of children born in 2011 to 1.3 percent of children born in 2015, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). While that rate is still low, it’s a worrisome trend. It also doesn’t account for the many cases of families who have their children vaccinated against some, but not all, of the diseases on the recommended schedule.

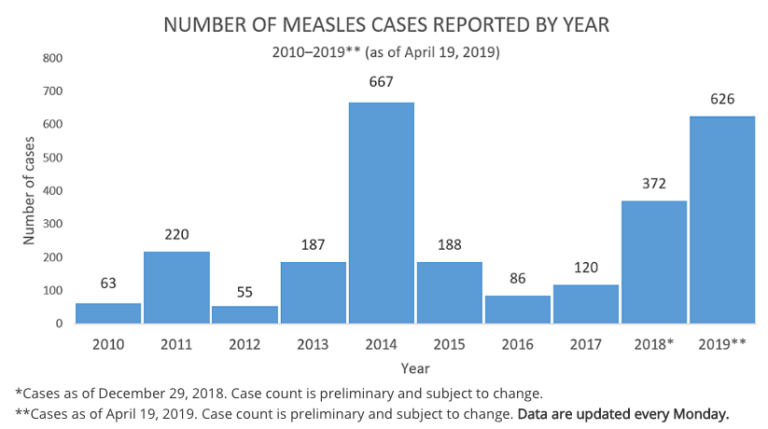

Lower vaccination rates have directly led to outbreaks of diseases that were thought to have been almost entirely eliminated. From January 1 to October 3, 2019, 1,250 individual cases of measles had been confirmed in 31 states — the greatest number of cases reported in the United States since 1992. More than 100 of the people who got measles so far this year had to be hospitalized, and 61 experienced complications including pneumonia and encephalitis (inflammation of the brain).

UNICEF is concerned about a possible resurgence of several other diseases, including pertussis (whooping cough), diphtheria, and mumps.

Unfortunately, if the trend of vaccine hesitancy continues, more illnesses that had become rare or almost nonexistent will resurface. More people will become sick. More people will die.

THE PROBLEM WITH NON-MEDICAL VACCINE EXEMPTIONS

There are valid medical reasons, described above, for some people to avoid some vaccines. But many other people avoid vaccines — for themselves and their children — for non-medical reasons. They may hold religious beliefs against immunization or may simply be frightened by misinformation they hear about vaccine risks and decide they personally don’t “believe” in vaccines.

But vaccines are so important to public health that communities cannot afford to let people avoid vaccines for non-medical reasons. Vaccine hesitancy puts the health of entire communities at risk, endangering the lives of the most vulnerable people among us, including young children, older adults, and those who are very sick.

The Power of Herd Immunity

People who have medical reasons for not being vaccinated depend on the vaccinations of others in the community to protect them. They need to be protected from disease as much as — or even more than — people with strong immune systems who can be vaccinated. In order to protect these vulnerable community members from getting sick, a critical mass of a population needs to be immunized.

If no one in a community is vaccinated, an illness can move through a population unchecked. But if too small a proportion of the population is vaccinated, an illness can similarly spread. The disease moves easily through the population, affecting many or most people who didn’t receive the vaccine. Those with a compromised immune system are especially at risk from illness.

In order to stop a specific disease from spreading, experts have determined that at least 95 percent of a population needs to be vaccinated against that disease. At that point the population has achieved what is called “herd immunity” — immunity for the entire population, regardless of whether or not they’ve been vaccinated. Once that goal has been reached, the spread of disease can be effectively stopped.

Unfortunately, unfounded mistrust of vaccines is making that 95 percent vaccination rate harder to achieve in many areas of America. The CDC found that the vaccination rate for the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) injection in kindergarteners in the 2017-2018 school year had slipped nationally to 94.3 percent — the third consecutive year that it dropped. As this number keeps getting lower, more and more Americans will get sick and face life-threatening complications.

Currently all but five states permit vaccine exemptions based on personal and/or religious beliefs. Those exemptions are putting entire communities at risk.

The Growing Threat of Non-Medical Exemptions

Non-medical exemptions have increased in the past 10 years. In New York City, where people are in close contact with others every day, it’s estimated that more than 250,000 people — in a population of 8.5 million — are unvaccinated. This number doesn’t include those who are medically unable to receive vaccines. As a result, areas of New York City have recently experienced measles outbreaks, as have numerous other communities throughout the United States.

THE BASICS OF VACCINE SCIENCE

What Vaccines Are — and What They’re Not

Much of the fear about vaccines is a result of misinformation, including discredited medical research. Vaccines do not introduce disease-causing organisms into the body, and they are not toxic drugs.

Vaccines spur the body’s own immune system into producing antibodies, or proteins, against a specific disease-causing organism, before the body is actually exposed to that disease. That gives the immune system a head start so that if it ever does encounter that organism in the future, it can eliminate the germ from the body before it has a chance to cause illness.

Someone may get vaccinated against polio and never be exposed to the virus that causes that devastating disease. But if they are exposed, they’ll most likely never know it. The polio vaccination they received as an infant taught their immune system to identify the virus as a foreign invader and destroy it quickly. Think of vaccines as an insurance policy, or to channel the motto of the Boy Scouts of America, a way for the body to “be prepared.”

How Vaccines Work: The Two Types

Vaccines either contain “dead “(inactivated) or “live” (weakened) parts of a microscopic disease-causing organism.

When the immune system is exposed to a vaccination, it creates a response against these parts of the microbe and programs the body to fight against it. This newly created defense system remains in the body ready to fight if the body is exposed to the microbe, making the person who’s been vaccinated immune to that infection.

Think of it like disassembled parts of a car. If you have only a front axle or a transmission, there’s no way you could put a whole car together. Vaccines can’t cause the illness they’re trying to prevent — a common misconception — because they contain only parts of the germ, not the entire organism.

Examples of dead/inactivated vaccines include:

- Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (DTaP)

- Hepatitis A

- Hepatitis B

- HPV

- Meningitis

- Polio (shot only)

- Pneumonia

- Tetanus

Examples of weakened/live vaccines include:

- Measles/mumps/rubella (MMR)

- Chickenpox

- Smallpox vaccine

- Yellow fever

Some vaccines, including those for shingles and flu, are available in both dead and live forms.

Some vaccines never change (such as MMR), and therefore, it usually just takes one or two vaccines in a lifetime to protect against these diseases. But there are other illnesses, such as influenza, that are caused by different strains of organisms each year, so a yearly vaccine is needed for protection.

Vaccines for Every Life Stage

Childhood

Many vaccine-preventable diseases are highly contagious. Children are even more susceptible to these diseases and infections because their immune systems are not as mature as an adult’s. It’s not that children’s immune systems are weaker, but that they haven’t yet been exposed to as many germs and allergens as adults, and therefore haven’t had a chance to build up immunity.

However, this does not mean that children’s immune systems aren’t strong enough for vaccines. In fact, the opposite is true: Vaccines are very beneficial to children’s immune systems and overall health. All FDA-approved vaccines have gone through extensive clinical trials for safety and effectiveness.

Vaccinating children not only prevents them from getting sick with the specified disease, but helps to build and strengthen their immune system. It also helps protect other children —friends, peers at school, neighbors — from getting sick as well.

Adulthood

Vaccination doesn’t end in early childhood. There are booster shots recommended for older children and adults (tetanus and diphtheria every 10 years). Some vaccines are specifically recommended for older adults (shingles after age 50, pneumonia after age 65). A flu vaccine is recommended every single year.

Travel to High-Risk Regions

People traveling to certain areas of the world may need specific vaccinations to protect against illnesses prevalent there.

Pregnancy

Pregnant women also need vaccines. The CDC recommends that pregnant women receive both the flu vaccine and the whooping cough vaccine during pregnancy. These vaccines transmit antibodies to the fetus, which is important since babies can’t develop their own immunity or be vaccinated against these diseases right away. Unfortunately, it’s estimated that only about a third of pregnant women get both vaccines during pregnancy as recommended. Flu can cause serious complications during pregnancy. In recent years almost three-fourths of the deaths from whooping cough in the U.S. have occurred in babies under two months old.

Understanding the Vaccine Schedule

The list of recommended vaccines and when you should receive them is called a vaccine schedule. In the United States, the vaccine schedule for children calls for them to be protected against 14 diseases in the first two years of life. This schedule has been carefully developed to work with children’s developing immune systems and protect them as soon as it is safe and effective against dangerous diseases they may be exposed to. The schedule does not overload children’s immune systems or put them at risk of illness. The opposite is true: Following the schedule exactly is the best way to keep children healthy and protected from illness.

Who Should be Vaccinated — and Who Shouldn’t?

Vaccines work along with a healthy individual’s immune system. Everyone with a healthy immune system should follow the recommended vaccination schedules. People whose immune systems are compromised may not be able to receive some vaccinations, especially live ones. This medical exemption may include people who have autoimmune diseases, people who take certain medications, or newborn babies whose immune systems aren’t mature enough yet for vaccinations. Your health care provider can advise whether or not certain vaccines are safe for you.

Medical contraindications — reasons not to get vaccinated due to medical conditions — can vary by individual vaccine. They also leave a lot up to the judgment of the doctor providing the vaccine. The body that issues vaccine guidelines is the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Read more here about their general principles for vaccine contraindications.

Keep in mind that because “the majority of contraindications and precautions are temporary, vaccinations often can be administered later when the condition leading to a contraindication or precaution no longer exists,” according to the ACIP.

FACTS ABOUT VACCINES

1. Vaccines emphasize prevention over treatment

The goal of medicine has always been to cure disease. But preventing it in the first place is even better. Unlike medications that are prescribed once someone is sick, vaccines help prevent specific illnesses from occurring in the first place. Like exercising and eating healthy, getting vaccinated is preventive care taken to avoid disease. Vaccines are one of the most convenient, effective, and safest preventive care measures available, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

Vaccines help prevent the specific diseases that they are designed to prevent. Getting vaccinated against measles, for example, almost completely eliminates the risk of getting that disease or infection. As a bonus, many vaccines protect against more than the specific infection they’re designed to prevent:

HPV

The HPV — human papillomavirus — vaccine, for example, protects against some forms of HPV, the most common sexually transmitted infection. But HPV is also associated with certain cancers. Vaccination against HPV prevents not just infection with the virus, but also the future risk of certain cancers, including cancer of the cervix, vagina, penis, anus, and oropharynx (back of the throat, including the base of the tongue and tonsils). Almost all cervical cancer is caused by HPV infection.

Hepatitis B

The hepatitis B vaccine protects against the hepatitis B virus — and also prevents a lifetime of chronic liver infections and/or liver cancer that can result from that infection.

Flu

The influenza vaccine protects against flu and also reduces the risk of pneumonia, an even more serious respiratory illness that can sometimes be a complication of flu infection. (There is also a pneumonia vaccine, but it’s generally recommended only for people over age 65 or those with compromised immune systems who would be at great risk from a pneumonia infection.)

2. Vaccines have saved millions of lives

Vaccines protect entire populations by targeting diseases that cause illness or complications, or even result in death. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), vaccines have prevented at least 10 million deaths between 2010 and 2015. Many more millions of people were protected from illness.

In the United States, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said in 2014 that childhood vaccines will prevent an estimated 21 million hospitalizations and 732,000 deaths in children born in the previous 20 years.

Most of the diseases for which children now receive vaccines have been reduced by more than 90 percent. In some cases the diseases have been eliminated or reduced by 99 percent.

There is a deadly cost to avoiding vaccinations. According to the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, each year in the United States about 50,000 adults die from diseases that could have been prevented by vaccination.

3. Vaccines protect more than just those who are vaccinated

Vaccines protect the children and adults who receive them as well as others in the community who have medical issues that may prevent them from being vaccinated.

People who visit a pediatric cancer treatment facility, for example, must have received a flu vaccine before they are allowed to enter. That’s because children being treated for cancer aren’t always able to receive vaccines. They’re dependent on everyone around them to be vaccinated in order to prevent the spread of disease and risk their already fragile lives.

The same is true outside of hospitals as well, where there are people in the community who can’t be vaccinated. The chickenpox and measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccines are recommended for children between 12 and 15 months old, so babies younger than that are vulnerable. Anyone who has had a severe allergic reaction to a vaccine may not be able to get that vaccine again. People who are sick at the time they’re supposed to be vaccinated may have to wait until they recover to receive the vaccine, depending on the severity of their symptoms.

Vaccines are one way that people in a community take care of themselves and of those around them. Being immunized is part self-protection and part of being civic-minded.

That is why it is so important for as many people as possible to receive recommended immunizations. And that is why it is so troubling that there has been a recent increase in people reacting to misinformation and becoming suspicious of vaccines. This unfounded fear — dubbed vaccine hesitancy — has already resulted in significant outbreaks of measles around America. Measles is not a harmless childhood illness. It is a very dangerous and contagious disease. Symptoms can be severe and include pneumonia, hearing loss, brain damage, and even death.

4. Vaccines have transformed public health around the world

We take for granted the health we enjoy because of how many diseases have been eradicated or controlled by widespread vaccination programs. Smallpox, the only disease ever eradicated worldwide, was eradicated using a vaccine. Vaccines have nearly succeeded in eradicating polio, a devastating virus that affects the spinal cord and brain, causing paralysis.

Edward Jenner, the British physician and scientist who in 1796 developed the world’s first vaccine (against smallpox) is sometimes considered to have saved more lives than any other person in history. The word vaccine actually comes from Dr. Jenner’s term for cowpox, a livestock disease related to human smallpox.

More recently Maurice Hilleman, PhD, (1919-2005), an American microbiologist who developed more than 40 different vaccines, has been said to have saved more lives than any other scientist of the 20th century. Of the 14 immunizations that are routinely recommended on U.S. vaccine schedules for children, Dr. Hilleman developed eight of them, including measles, mumps, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, chickenpox, meningitis, pneumonia, and influenza.

In some ways, vaccines have been a victim of their own success. It’s easier to believe that something is unnecessary when there’s no memory of how much worse life was like before it existed. It’s hard to imagine anyone who can recall friends or family members with polio trapped in iron lungs for survival choosing to opt out of receiving the polio vaccine.

But, tragically, vaccine hesitancy is changing all of this. After years in which most young U.S. doctors had never seen a case of measles, there have been over 1,200 measles cases reported in the United States from January to October 2019 — the worst outbreak since 1992. A recent measles outbreak in the Pacific Northwest in 2019 included at least 101 cases. There were more than 600 confirmed cases of measles in New York City between September 2018 and August 2019.

To put that in perspective: In 1941 there were almost 900,000 cases of measles in the United States. In the year 2000 there were only 86. It is very worrisome that the number of measles cases has begun to climb.

This year, the World Health Organization (WHO) listed vaccine hesitancy as one of the top threats to global health.

DEBUNKING THE DANGERS OF VACCINES

Anyone with school-age children has likely heard other parents’ objections to having their child vaccinated. That misguided decision puts many people at risk. It is important for you to be armed with facts in order to counter those objections and misconceptions.

Here are some common reasons people give for avoiding vaccines — and why they’re wrong.

Myth: You can get sick from a vaccine

Unless someone has a very compromised immune system — which is a medical condition — the human body is built to work with vaccines. Examples of people with compromised immune systems include people with cancer, undergoing chemotherapy, diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, sick with tuberculosis, and taking medications that suppress the immune system.

Catching a few colds each winter does NOT mean that someone has a weakened immune system. Unless someone has a medical condition that causes weakened immunity, vaccines are safe and effective. Vaccines are made from weakened or killed organisms that cannot cause illness in a healthy immune system. In fact, vaccines work with the immune system to make it even stronger and more protective. Anyone worried about a child’s health or immune system status should consult a pediatrician.

Some people experience side effects after receiving vaccines, including mild redness or swelling at the injection site, a low-grade fever, drowsiness, and/or rash. But these typically go away on their own in a day or two. These minor reactions do not mean that a vaccine has caused illness. The flu vaccine cannot give you the flu.

Myth: Vaccines can cause autism and other illnesses and disabilities

There is no scientific evidence to support this claim. The original research that suggested this link has been more than just rejected — it’s been labeled as falsified and fabricated data. The author himself has come forward to denounce the research.

All vaccines have gone through rigorous clinical trials. They have all withstood the strict regulations set by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA). All vaccines have been scientifically deemed safe and there is no sufficient evidence to suggest otherwise. This includes the misbelief that vaccines cause autism or that vaccines can overwhelm a child’s immune system.

The anti-vaccine movement that spreads this misinformation is a highly effective interest group that is not supported by scientists and public health experts.

Myth: If most people get vaccinated and most of these diseases have been reduced so much already, then it’s not necessary to risk having my child vaccinated

While vaccines have reduced most vaccine-preventable diseases to very low levels in many countries, including the United States, there are still some diseases that are prevalent or even epidemic in some parts of the world. People who travel may unknowingly transport disease from one country to another. Without proper vaccination, such diseases can quickly spread.

Vaccines work through herd immunity — which means that unless at least 95 percent of a population is protected against a specific disease, there may be outbreaks of that illness, which can quickly spread. That is what has been happening recently with measles in the United States. That is why it is crucial that everyone who can be vaccinated stay up to date with vaccines — to protect themselves from illness and to protect more vulnerable members of the community who cannot be vaccinated for medical reasons. That is the only way to make vaccine-preventable diseases disappear.

Myth: It should be a parents’ choice whether or not to vaccinate their child

There are some things considered so important for the public health of society as a whole that they are required of everybody living in that society. Children have to wear seatbelts or use a child safety seat while in a car. They have to wear helmets when riding a bicycle. Parents can’t decide not to secure their children in car seats just because they disagree with those laws.

Vaccines fall into this category. They are so essential to public health that they are required. Not vaccinating children puts those children plus everyone else in a community at risk.

Myth: Some vaccines, like the flu vaccine, don’t work very well, so there’s really no point

Like other medications, vaccines are carefully regulated and not able to enter the market unless they’re deemed significantly effective. Years of research need to prove that the drug or vaccine works. The FDA has extremely stringent rules and regulations to ensure that only effective and safe drugs enter the market. This is one of the reasons it takes years — 10 years or more on average — for prescription medications and vaccines to become widely available and why only one in 5,000 new drugs makes it to the market.

The flu vaccine is a slightly different case, since it must be reformulated every year to respond to global flu virus trends. Each year scientists monitor flu outbreaks around the world to try and predict which viral strains will pose a threat in their countries. They formulate the vaccine for that year to counter those specific strains of the virus.

Some years the predictions are more accurate than others, and the vaccine is more effective. The flu vaccine’s effectiveness also depends on the age and health status of the person getting the vaccine. In fact, stronger doses are recommended for people over 65, to spark a stronger immune response.

But getting the flu vaccine, as long as there are no medical contraindications, is always a wise choice. Even when the match between the vaccine and the viruses in circulation is less than ideal, getting vaccinated generally results in a milder case of illness if a vaccinated person is exposed to the flu.

Remember, the flu is not just a bad cold. The flu is a potentially deadly illness. The CDC estimates that in 2016-2017, the flu vaccine prevented an estimated 5.3 million influenza illnesses, 2.6 million flu-related medical visits, and 85,000 flu-related hospitalizations in the United States.

Concern: I’m not anti-vaccine, but I don’t think my child should get combination vaccines or get so many different vaccines at the same time.

The U.S. CDC vaccine schedule recommended for children has been carefully developed with scientific trials to identify the most effective and safe way to protect children. Scientific evidence supports the idea that simultaneous vaccination with multiple vaccines has no adverse effect on the normal childhood immune system.

These vaccines cannot overwhelm the immune system. The decision to space them out differently than the medically recommended schedule is a bad idea. Research shows that inappropriately spacing out or delaying vaccinations can be problematic because it means there’s a bigger window of time when a child is unprotected.

Spacing out vaccines does not protect children. It actually puts them at greater risk of disease.

Concern: It’s not the virus but the chemicals in vaccines I’m worried about.

One recurring concern is that some vaccines, such as the influenza (flu) vaccine, contain mercury in a form called thimerosal, used as a preservative. But unlike the mercury that’s ingested when someone eats certain types of fish, the mercury in vaccines doesn’t remain in the body and is quickly eliminated. No link has even been found between this preservative and autism.

Thimerosal was taken out of U.S. childhood vaccines in 2001, according to the CDC. Removing thimerosal seemed to have no effect on the rate of reported autism cases in the U.S., which continue to rise. In 2004 an estimated one in 166 8-year-olds were diagnosed with autism, while based on 2014 data the CDC estimated that in 2018 that number would rise to one in 59, according to Autism Speaks.

Common vaccines like the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella), varicella (chickenpox), inactivated polio (IPV), and pneumococcal conjugate do not contain any mercury and have never had any mercury.

Thimerosal, which has been deemed safe by the FDA, is only used in vaccines when considered necessary to the vaccine’s safety and effectiveness. Only a few vaccines still contain thimerosal as a preservative, including some versions of the Influenza (flu) vaccine, which are currently available in both thimerosal-containing (for multi-dose vaccine vials) and thimerosal-free versions.

The thimerosal was not removed from childhood vaccines because of fears of autism, but rather to reduce lifetime exposure to mercury.

Drugs, medications, and vaccinations are not approved by the FDA if any piece or part of the drug is harmful or ineffective, or even just not effective enough. Vaccines, like any other medication that enters the market, go through years of research and multiple phases of clinical trials to ensure their safety and effectiveness.

ABOUT US

The Global Healthy Living Foundation and the 50-State Network advocate for patients with chronic illness and autoimmune disease. While the advocacy comes in many forms, all are geared toward improving the quality of life and health and well-being for people with and without chronic illness. The organization understands and respects different philosophical and religious beliefs but believes that in order to maximize vaccination success and immunity for the public as a whole — and especially for those with chronic illness and autoimmune disease—vaccine exemptions should only be permitted for valid medical reasons.

Join the 50-State Network to advocate for vaccines with us.

If you would like to advocate for improving vaccination policy and/or have a story you would like to share that relates to inadequate vaccination rates, please reach out to GHLF.

MORE INFORMATION AND RESOURCES

https://www.vaccines.gov/basics/safety

https://www.who.int/immunization/programmes_systems/vaccine_hesitancy/en/

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/appendices/B/us-vaccines.pdf

https://www.hhs.gov/vaccines/national-vaccine-plan/vaccine-safety-scientific-agenda/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/ensuringsafety/monitoring/index.html

https://www.vaccines.gov/basics/safety

https://www.aafp.org/afp/2017/0615/p786-s1.html

https://www.aafp.org/afp/2002/1201/p2113.html

https://www.immunize.org/resources/part_us.asp

https://www.ahip.org/vaccines-save-lives/

https://www.apha.org/topics-and-issues/vaccines

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6740a4.htm?s_cid=mm6740a4_w

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/contraindications.html

SUBSCRIBE TO GHLF

Advocacy News

_

Was this article helpful?

YesNo